Note 2 - Calls and Puts

Table of Contents

A Brief Recap

In the last note, we learned how put options can be used to hedge long positions, and how call options can be used to hedge short positions. In this note, we will examine raw options, or their intrinsic values without being used as a hedge. After that, we will take a brief overview of some factors impacting their valuation.

Value of Options

Put Options

Put options, as we originally learned, are used to hedge a long position. In other words, they only take on value when the underlying stock decreases in value past the strike price. To get an intuition for why this is true, think about it as an insurance. If the value of the underlying doesn’t fall, this means that the insurance is as good as worthless – it doesn’t give you any value. However, once the value of the underlying falls, this means that the option is now giving us protection, or added value. Again, an example:

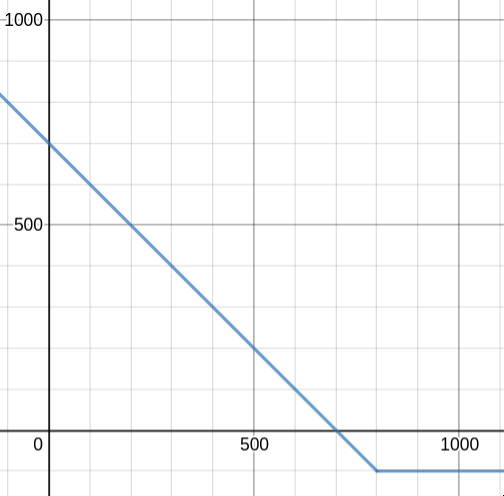

As a reminder, the example from the previous note was buying a $8 put option costing $1 premium. With that same example, we see that for every dollar the underlying stock falls under $8, the option’s value gains $1. Otherwise, if the stock remains above $8, the option has no value at expiration1, which would mean a loss on the premium, or $1. Here’s the graph:

\[V = \begin{cases} -$100 & ,S \geq $800\\ -$100 + ($800 - S)= $700 - S& ,S < $800\\ \end{cases}\]

Call Options

Call options are the opposite of put options, giving us defined risk on shorts instead of longs. Therefore, let’s directly jump into an example:

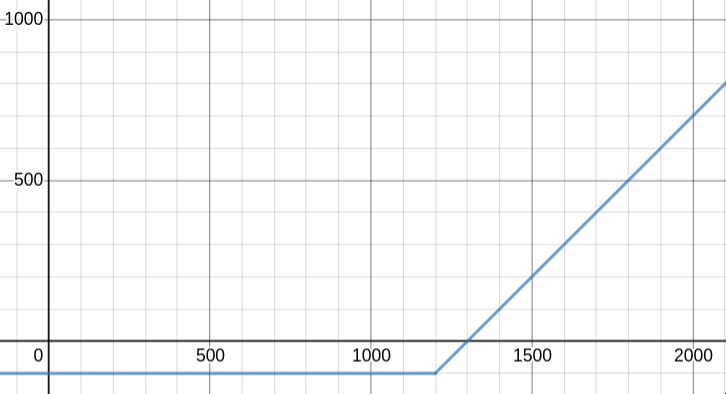

As a reminder, the example from the previous note was buying a call option at the $12 strike for a $1 premium. We see that, at expiration, with every one dollar that the stock increases past $12, the option gains one dollar. If the stock remains below $12, the option has 0 value, so it would be a loss for the entirety of the premium.

\[V = \begin{cases} -$100 & ,S \leq $1200\\ -$100 + (S - $1200) = S - $1300 & ,S > $1200\\ \end{cases}\]

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Value

You might have noticed that I said “at expiration” many times throughout this note, and you might be wondering why that was necessary. It turns out the value of an option has several factors, one of which is time to expiration, so it’s actually very necessary, when talking about the price of an option, to look at the exact time we’re referencing.

The price of an option is composed of extrinsic value and intrinsic value. The intrinsic value of the option is the value we graphed above – it’s the value the option inherently has as a result of being an “insurance”. The extrinsic value is any additional value placed on top of the option. Let’s develop some intuition for why there even exists an extrinsic value in the remainder of this note, and in the next note, we will look more thoroughly at all the components making up extrinsic value.

Extrinsic Value

Where does extrinsic value come from? Let’s go back to our simple house example, and think from the perspective of an insurance company. How do you imagine they price the insurance on the house? Why might a two-year insurance cost more than a one-year insurance, which in turn might cost more than a one-day insurance? These differences in pricing is all coming from the extrinsic value of the different insurances. In short, the more volatile the underlying is – in the case of insurance, the more your house is prone to flooding – and the more time there is, the more likely it is for some bad event to happen, causing the insurance to come into effect. As a result, the extrinsic value will be inflated, and the insurance will be priced higher. Think of the extrinsic value as a “buffer” that is, in essence, a value placed on additional risk.

Footnotes

-

Don’t worry about what “at expiration” means at the moment. We’ll learn later that time to expiration is part of the pricing model for options, but it’s too complicated to talk about all at once. ⤴