Covid-19 and Game Theory

With the Coronavirus, tissue paper and supplies are flying out of stores. Some argue that it’s a natural human reaction best explained by Game Theory. In this essay, I will explore these claims, as well as how several countries have responded differently, and how their policies can be explained by Game Theory.

N.B.: This post was originally the essay for one of my Stat 155 assignments. I thought it interesting enough to share on my blog – I hope you enjoy it!

Articles Referenced and Their Claims

In The Herald1, the Adam Smith Institute2, and Asia Times3, the authors argue that the situation is well-explained by Prisoners’ Dilemma. In The Herald, McArdle makes the additional claim that Western countries have a lack of trust that Eastern countries do not have, exacerbating the Prisoners’ Dilemma problem. Macdonald of the Adam Smith Institute makes a particularly astute economic observation that “raising prices in our current context is not a cynical cash grab, but an effective means of restoring consumer confidence and ensuring we can all access the goods we need during these strange and difficult times”.

A minor charge can be compared to temporary economic and material disruption. That would have been the sole significant setback had corporations cooperated. In this case the entire economic machinery would have toned down and shrunk, and thus everyone would have been affected more or less the same.

The problem, however, arises when some parties betray the faith. From a single corporation’s or businessman’s point of view, if they stay faithful, and other parties do not adhere to the bargain, they fall back in the competition. The disadvantage sustained could very plausibly be insurmountable, akin to one prisoner walking off free while the other suffers a massive loss.

– Kaushik, Asia Times

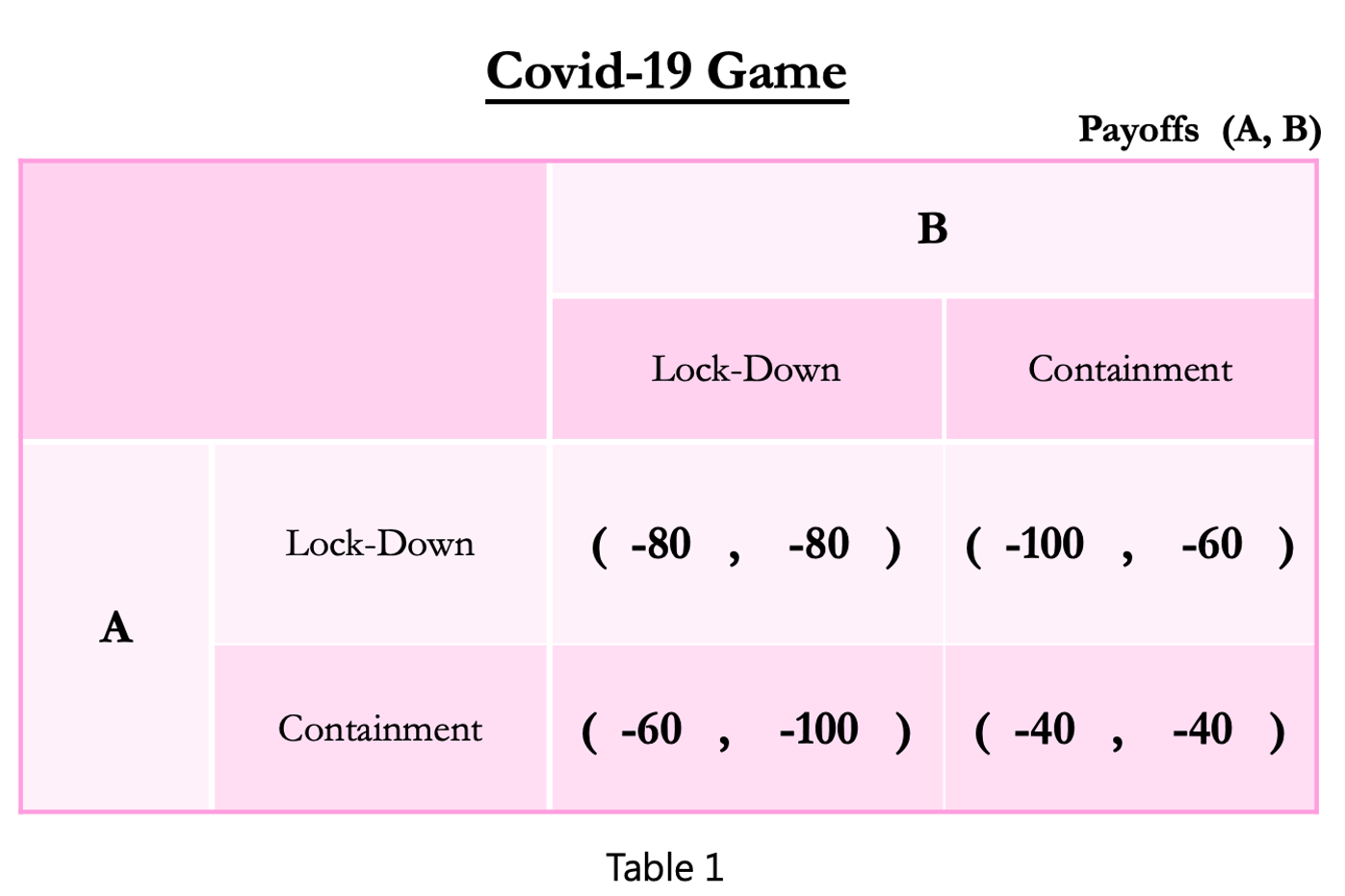

In an article published on Medium, Fang tackles a popular post floating on Facebook claiming to explain the Coronavirus in terms of Game Theory by arguing that the explanation was flawed due to a wrong application of said theory. Fang then reproduces the game, this time with her own chart. Noticeably, the chart, reproduced below, has a Nash Equilibrium that is Pareto Efficient!

Prisoners’ Dilemma

But are we as humans really stuck in a game of Prisoners’ Dilemma? Seeing that several Asian countries, and Taiwan in particular, have no issues with hoarding, we must either settle for the conclusion that humans are fundamentally different across the East and the West, as McArdle claims, or that there is some other factor at play impacting the setup of the game itself.

In the situation where the setup of the games are the same, where both the East and West are facing Prisoners’ Dilemmas, the lack of shortages in the East would mean that the people are cooperating. While plausible, these differences must necessarily be attributed to a difference in culture, meaning that scarcity would manifest differently across the United States. Seeing that communities everywhere see shortages, there must be some other explanation.

Suppose for a moment that supplies are not scarce; ie. no matter how much toilet paper one buys, another will not be impacted. Denote the payoff of hoarding to be \(-5\) due to diminishing returns, and the payoff of not hoarding to be \(0\).

\[\begin{bmatrix} P1 \textrm{\\} P2& \textrm{hoard} & \textrm{don't hoard} \\ \textrm{hoard} & (-5, -5) & (-5, 0) \\ \textrm{don't hoard} & (0, -5) & (0, 0) \\ \end{bmatrix}\]In this setup, we immediately see that the Prisoners’ Dilemma problem has disappeared – \(\textrm{(don't hoard, don't hoard)}\) is the Nash Equilibrium and the Pareto Optimum, meaning that with a lack of resources, there is no incentive for anyone to hoard resources! This makes sense – why hoard knowing that resources will always be available when you need it?

Response to the Coronavirus

Let us take a step back and view responses to the coronavirus; in particular, we compare Taiwan’s4 approach to the United States’5.

On December 31st, 2019, both the United States and Taiwan learned about the cases in China. On that same day, Taiwan started inspecting inbound flights from Wuhan, while the United States waited until much much later. Mask rationing was implemented on February 6th, with the Taiwanese Armed Forces deployed to aid the scaling of mask production in factories. In the United States, people were recommended to not wear masks, claiming that their efficacy was unproven and limited. In the third week of February, medical experts “concluded that the United States had already lost the fight to contain the virus”.[^nytimes-red-dawn] Contrasting this is the efforts of Taiwan, who as of today only have a mere 395 cases (fewer than my county!) and are exporting face masks!

Arguments as to why Taiwan and other countries’ responses have been so quick are varied, including the fact that they have seen SARS, a similar virus and situation, but one thing is clear: their people have much less to fear when they know that containment is quite evident and adequate. This effectively reduces their situation to the lack of shortage situation discussed earlier, since they can depend on supply chains not shutting down because of adequate preparation.

Facing the Shortages

But are people acting irrationally? At a collective level, it is leading to shortages of goods. But in a direct sense, people are acting rationally. It becomes optimal rather than suboptimal to start stockpiling if everyone else does because their stockpiling creates the very supply problem they are trying to avoid in the first place.

– Macdonald, Adam Smith Institute

I was an intended Economics major prior to switching to Statistics. Macdonald’s claim piqued my interest, so let’s examine them through a statistical lens.

In the situation where market values are not restricted, we have the following payoff diagram: In the case where people both do not hoard, there is no change from the status quo, so the payoff to both is 0. In the case where one hoards and the other doesn’t, one gains and the other loses. In the case where both hoard, there is a small loss to both (since there is a loss of accessible resources in the case either need them). This is classical Prisoners’ Dilemma:

\[\begin{bmatrix} P1 \textrm{\\} P2& \textrm{hoard} & \textrm{don't hoard} \\ \textrm{hoard} & (-2, -2) & (3, -3) \\ \textrm{don't hoard} & (-3, 3) & (0, 0) \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Now, suppose there is a price floor imposed on the market, equivalent to the total marginal utility gained through hoarding beyond the original market equilibrium. The scenario is the same, with one changed parameter: hoarding is more expensive now, incurring a loss of \(-3\). We define a new field, \(\textrm{hoard less}\), describing a situation where hoarding is in effect, but with less quantity. Assuming that both people have a price-elastic response6:

\[\begin{bmatrix} P1 \textrm{\\} P2& \textrm{hoard} & \textrm{don't hoard} \\ \textrm{hoard} & (-5, -5) & (0, -3) \\ \textrm{don't hoard} & (-3, 0) & (0, 0) \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Immediately, we see that we have recovered a situation with the Nash Equilibrium equal to the Pareto Equilibrium equal to not hoarding for both. In other words, the market price floor has a positive effect in this scenario.

Footnotes

-

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/18314703.helen-mcardle-game-theory-tells-us-britains-reaction-coronavirus/ ⤴

-

https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/covid-19-and-game-theory ⤴

-

https://asiatimes.com/2020/03/covid-19-and-the-prisoners-dilemma/ ⤴

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_coronavirus_pandemic_in_Taiwan ⤴

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_2020_coronavirus_pandemic_in_the_United_States ⤴

-

Here, I make a key assumption that price elasticity of hoarded goods are elastic beyond their basic consumption. The author of the Adam Smith Institute article, Macdonald, has observed anecdotally that his experience supports this conclusion. ⤴